Interview with Paulo César Pereira, an Afro-futurist teen

“There are essential things you need to know about me. Things that, if I were to explain myself to you one day over three minutes in an elevator, I could not fail to mention [imperceptible pause, change of tone]. Hi, I’m Paulo, I’m 17 years old, and it’s a pleasure to be here with you in this elevator.”

It took me a second to catch up. Just like that, Paulo had transported me from my Skype interview screen into that elevator with him. Over the next, not three, but sixty minutes, this charismatic Afro-futurist teen called Paulo would take me on a journey through space and time.

First stop: Favela do Jaguaré, the neighborhood in the periphery of São Paulo where Paulo grew up. “When my family came from the interior of the state to the big city, they settled into the most comfortable place to live, which was not a rich place. It was poor but cozy and welcoming to everyone coming from everywhere. The favela, my dear, is where you will certainly find people from all over Brazil… and every three or four blocks, you are bound to find someone from my family, a Pereira!”

With this tone of sensible humor, Paulo led the rest of our journey. “My favela is not the glamorous kind you might see in soap operas. Unfortunately, its crime levels are a bit more… ‘active’ than normal. But it is also a place filled with ‘social opportunities,’ and this is the theme of the story I’m about to tell you.”

“Get this: when you grow up in a favela, you grow up as a being who is ‘inattentive’ to the things that happen outside your bubble. That’s because, when you are born a favelado, almost everything that comes from ‘the outside’ is a slap in the face… so you end up shielding yourself, throughout your life, from everything external, including opportunities. That’s how I was, too, for a long time.”

Until he realized that in his favela, there were “social projects,” and he decided to join the one that involved theater – Projeto Palco. Four months in, his theater company received an invitation to participate in a theater festival at Graded American School, one of São Paulo’s most elite private schools.

“I said to myself, ‘what is this?! A theater company full of favelados who were acting for the first time in their lives getting invited to an American theater festival at a gringo school?’” Paulo was excited. But the rest of his troupe was not convinced. On the day of the festival, Graded sent an entire bus to pick them up, and only four actors got on. Paulo was the only one who spoke English, which he’d taught himself from a dictionary left at his dad’s bakery one day.

Against the odds, they performed a four-minute skit that won first place in the entire festival! Remembering that moment with a huge smile, Paulo said, “that was the moment in which I recognized myself for the first time as a favelado, as the person I was. Because get this: the invitation to the festival made it clear that your skit could be in any language. So, when we were writing ours, especially due to its theme [of self-expression vs. societal norms] and the place from which we were coming, we decided that we would be able to convey the most meaning if we did not use any specific language.” Their skit was entirely wordless. “The only language we used that day was the language of art. The way we found to communicate with those people who not only spoke a different language from ours but who came from a completely different reality than ours was through art…. And, well, judging by the prize we won, I think this method worked perfectly!”

Paulo learned two things that day. First, he could “transcend those economic, social, and cultural barriers through art.” And second, that he “had a space in life.”

“I swear to you… that day I didn’t feel like ‘I won’t, I felt like I was literally looking back and seeing my entire quebrada, my entire community, behind me saying, ‘dude, we won!’ That day was a victory not just for my troupe or me but for our entire community. And I don’t mean the physical place where I grew up, but the social demands and causes with which I identify.” It was the first day he felt this way, and he has been “addicted to social impact” ever since. His particular method is to ‘go outward, to learn what’s inside,’ countering the more common behavior of not leaving the ‘favela bubble,’ which he comprehends is a mechanism of defense from outside blows.

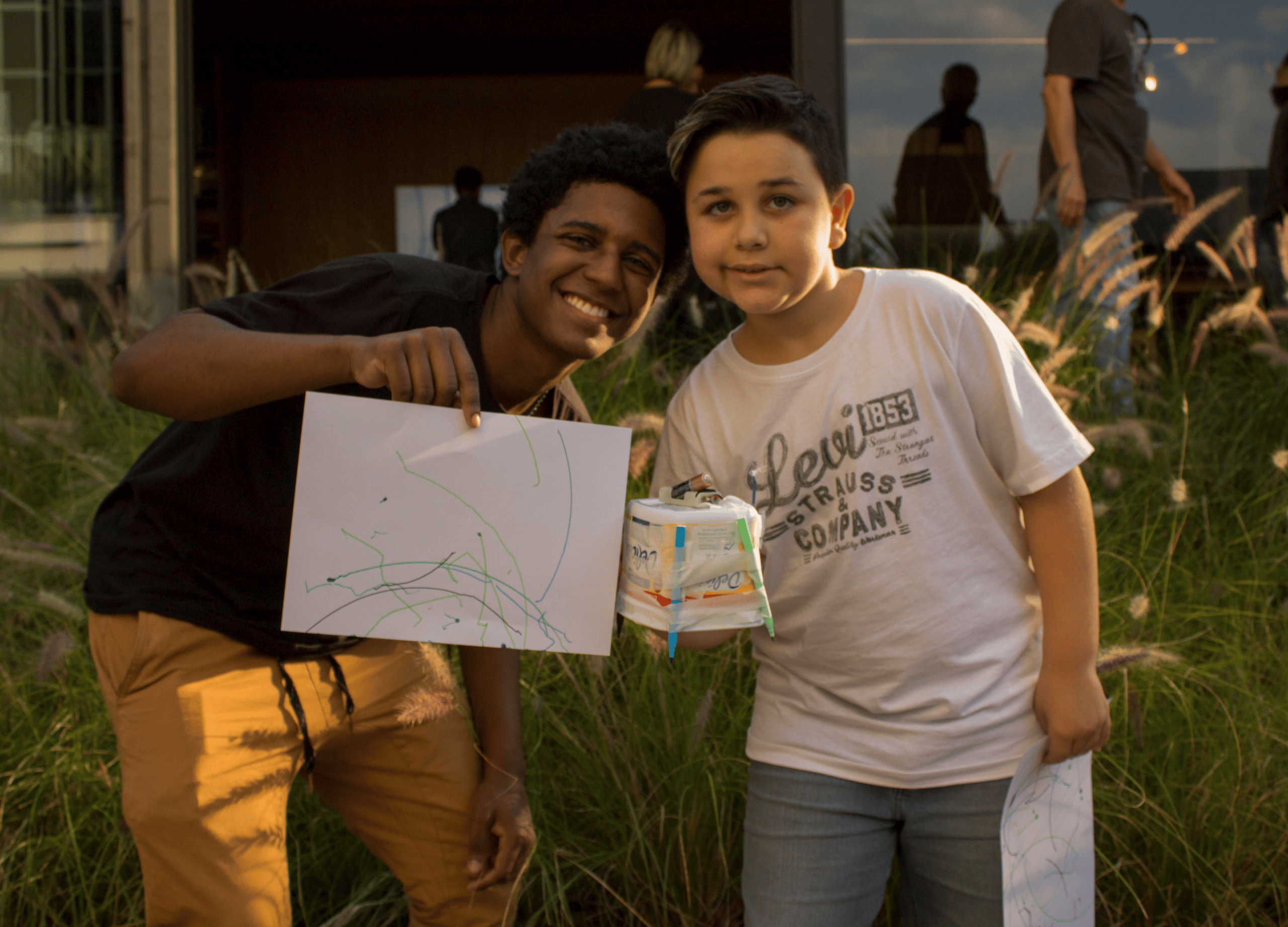

Driven by the mission of self-discovery and social impact, the next stop on Paulo’s journey was the makerspace of Projetistas Periféricos – a social project in Jardim Conceição, another peripheral neighborhood in São Paulo. There, Paulo met one of his heroes, the creative Miguel Da Hora, who got him hooked on futuristic education for the 4th industrial revolution: the concept that many current jobs are about to be replaced by technology and we must educate people with different socio-emotional and technological skills in order to be prepared. “Those who will pay the steepest price during this transition are, as usual, most socioeconomically vulnerable. In Brazil: people who are black, poor, and female… and this worries me because these are my people. We need to, in a very immediate time-scope, resignify work.”

Through Projetistas Periféricos, Paulo created Outskirts (an English teaching program); participated and won 3rd place in a Startup Weekend; learned and taught socio-emotional and robotics skills; and got close-up experience with Marias de Fábrica (MdF) – a social enterprise that trains single black women in using laser-cutters and 3D printers to make jewelry using scrap wood. All these experiences, along with Miguel da Hora’s mentorship, made Paulo look “even more outward,” helping him consolidate his goals within.

“I finally discovered what I want for my life. The quebrada has provided me with so much learning and knowledge… I always wanted to be a scientist, like an academic researcher, but that’s not taken very seriously here where I live. So, I’ve taken upon myself the following mission: to go abroad to study the topics I want, and then try to apply this to my quebrada somehow… At Projetistas we have a rule: ‘everything you learn there, you need to give back to the world.’ For example, if you learn about Stand Up Comedy at Projetistas, you have to turn it into an event or workshop for your community about comedy. So, I’ve taken it as my personal goal to transform everything that I will learn on my academic journey, wherever that is, into something I can give back to my quebrada.”

Right now, Paulo is part of the BRASA Pré mentoring program, which is helping him apply to U.S. universities. The topics Paulo wants to study in college are a blend of Afro-futurism and STS (Science and Technology Studies).

Afro-futurism is the cultural-artistic movement of re-imagining history without colonization and projecting Afro-centric futures (and sometimes pasts and presents) in which positions of power and technological advancement are led by black people. As Paulo describes, “Afro-futurism is about trying to externalize all the pain that black people suffer and, in its place, trying to reimagine ‘what if it was not just about blood, pain and constant battles? But about victories, especially from a technological and futuristic point of view?’” The most popular contemporary expression of Afro-futurism is the movie “Black Panther” with the technologically advanced society of Wakanda.

Paulo envisions applying Afro-futurism to tackle the current economic reality of poor black people’s jobs being displaced by the 4th Industrial Revolution. “Our historical moment is practically asking us to work with Afro-futurism.” In a way, the project MdF is an example because it has peripheric black women at the center of jewelry design using high-tech tools. Paulo is learning from them but plans to take a “slightly different approach” in his own work. While Miguel works with adults – folks facing imminent unemployment right now – Paulo wants to work with children and youth to prepare them for the future and guarantee that they have the necessary skills to deal with the 4th Industrial Revolution, using Afro-futurism as a foundation. “I want black kids in the quebrada to have the power of technology in their hands, so they can create things they care about.” In addition to tech skills, he also plans on teaching socio-emotional skills and using active learning methodologies.

Paulo sees that he is privileged to have had access to these tools. His “biggest dream” is that other black kids can have them too and that, together, they can do something about the issue. “This is something that personally affects me. I worry that my friends are now thinking about going to college and getting a diploma that may not serve them in the future… that all their hard work during adolescence will have been wasted. If I can do anything to change these, frankly, dismal future prospects, I’m going to do it.”

“This is the issue that has captured my heart, my mind, and everything I do right now. If I have the opportunity to go to the LALA pilot Academy next February, this the problem I would want to tackle there with all my efforts. I am more than ready to win over the hearts of everyone at LALA to work on this issue with me because this is the kind of cause that can only be addressed by working with many different people.”

Paulo has been admitted to the 2020 LALA pilot Academy. However, standing between him and his attendance is not only a sizeable fundraising target but an even heavier history of distrust between favelas and “things that come from the outside.” Paulo is unsure whether his family will allow him to go to Medellín. “I completely understand their position, given their life experiences… here in our community, those who dream big generally get, excuse me, screwed. My parents want the most realistic and comfortable scenario for me… Remember what I told you at the beginning of our conversation? That, when you are a favelado, generally, what comes from ‘the outside’ is a slap in the face, so you immediately distrust everything? Well, this is literally it.”